I’d been waiting for Challengers. It’s a film I want to talk about, but one which – I’ve found – has proven surprisingly difficult to write through here. This is, I think, often the case with the films Luca Guadagnino has directed. For a certain type of filmgoer, they appeal in a way almost primal: we like them. We want to like them. We arrive prepared to like them. Yet, loquacious as we may tend to be with our critiques, we struggle with finding the words to articulate precisely why we need you to understand these films feel – just a little bit – made for us.

When I initially started drafting this I found myself catching up on an episode of the podcast “This Had Oscar Buzz” in which hosts Joe Reid and Chris Feil attempted to work through the nuances of one of my personal favorites, A Bigger Splash, and stumbled almost immediately into the hornet’s nest that comes with applying language to what is – in some ways – a vibe. I wasn’t surprised when the hosts discovered they had radically different interpretations of character intentions, that they couldn’t actually put an agreed upon pin in where the film’s central thesis is, what moral alignment it might have, or – even – who emerges as a main character.

I wasn’t surprised to hear it, but I did laugh.

In listening to that episode, I started to think it spoke more broadly to what’s interesting about Guadagnino’s films: it tends to be incredibly easy to take them in as breezily sexy (sometimes bloody) romps. The characters often operate on frequencies just chaotic enough to be seductive, the situations at quietly art-house levels of debauched, and he chooses actors with a knack for wordlessly communicating types of fierce desire, of hunger.

This is the first level a Guadagnino film operates on, and – frankly – it’s enough. The podcast episode contextualized this for me: I love A Bigger Splash, more – shamefully, honestly – than I love the film it’s loosely adapted from (La Piscine). Yet when I recommend it to people, I always pitch it as the ultimate “rich people being terrible on vacation” film, a sun-soaked, debauched good time, and when friends watch it – that’s precisely what they enjoy. Launch into a conversation, though, and suddenly you’re in the mess Reid and Feil found themselves in: picking away at form, historical margin notes, or dynamic and troubling character psychology, of social critique and agonies of influence. There’s a tangle just below the surface, a labyrinth of possibilities and visible roads not taken, and the motor of each film is fueled by exactly this tension.

Challengers is no exception, though I have to admit my initial take – which is arguably maybe the right one – is that it’s silly and fun and drunk as fuck on its own horniness. One of the first release date casualties of the SAG-AFTRA strike, the removal of Challengers from the lead-up to Oscars season has freed it to live its best vacation self; the conversations largely centered on the summer-appropriate tenniscore fashion, Loewe t-shirts, Zendaya’s red carpet looks and the thumping techno absurdity of its propulsive Reznor/Ross score – sure to launch a million tik toks.

You could call it a love triangle movie, I guess, though the type of love at its core isn’t something we’d necessarily equate with the stuff of the Hollywood romance. As its title suggests, Challengers is adversarial, deeply combative, a tale of power dynamics and a deep-seated drive to retain the upper hand. The film follows three tennis players through volleyed time-skips; from the cusp of teenage, pro-ascension through stardom and to the verge of retirement (in the world of sports, a whopping 13 years). We enter the film with Tashi (Zendaya) and Art (Mike Faist) as a married couple, a dynamic duo with their faces plastered on a building-sized billboard ad for Aston Martin.

Tashi has become a manager, a coach to her Art Donaldson – her only client – after her own tennis superstardom crumbled as the result of an injury. What we can see – immediately – is what the game means to her versus Art; the way she lives it even as she can no longer play, and the way what’s emerging as either complacency or crisis for him solidly fucks what, for her, is the true point of their continued relationship. Art has been faltering, and so Tashi pushes him into a low-stakes endeavor; a challengers championship match in a upstate New York that she seems to hope will reconnect him with his own energized love of the sport.

The structure of the film is built around this present; a face-off we quickly realize is a sort of happenstance reconnection with Patrick Zweig (Josh O’Connor) an old adversary who also happens to be a former best friend and serious romantic rival for Tashi’s affections. He’s also a roguish figure, a down-and-out hustler with an apparent, self-serving amoral center. The visual staging of Donaldson vs. Zweig is blunt force with its obviousness; Tashi sits center court in the stands, Art on one side, Patrick on the other, and the film begins its rubbernecking back and forth; volleying relentlessly from past to present, from Art to Patrick, between the sexual lines of attrition and ferocious reunions and break-ups. It’s predictable and over-the-top and goofily funny and deliciously gossipy; its every mechanism all about pushing harder and going too far on the court becoming the very thing that makes it entertaining as fuck.

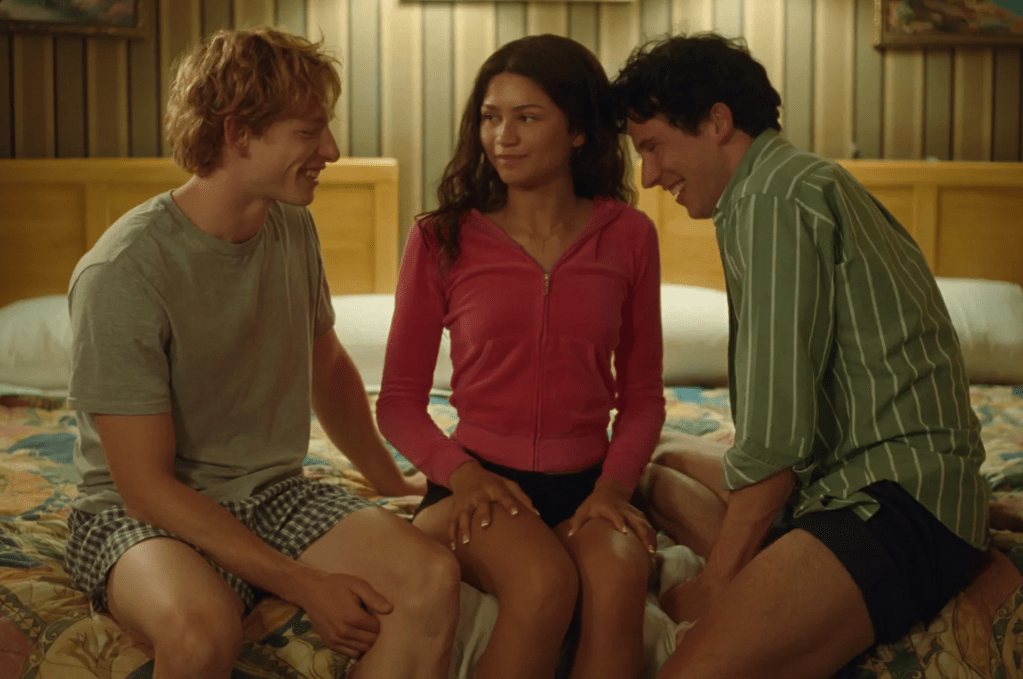

To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, everything in Challengers is about sex, except for the sex itself, which is power. As the film’s shot-caller, Tashi expresses this from youth, speaking to the screaming climax of the match Art and Patrick first see her play as an argument, its whole back and forth the playing out of an arc of a relationship. She’s aggressive in all facets of life, someone with a need for control she tends to flex just to prove her dominance; a tendency emerging in the film’s memorable, near screwball dalliance towards a hotel threesome, in which Tashi manipulates the friends into passionately making out with one another, playing out something she and the audience recognize as the undercurrent of their tension. Tashi gets off – she tells us as much – on watching some really good tennis. It’s damn near a kink.

This is roughly where the Guadagnino gulf of it all opens its gaping maw; the film is doing a lot. Much of it becomes structurally obvious; the too-cleverness of modeling the narrative after a tennis match underlining the hand offs of the upper hand in a way easily translatable as enough. On top of that, too, all three actors have movie star charm, O’Connor and Faist’s relative unknownness working in their favor to undercut anything not serving the flirtatious tensions on screen. You can love the film for that; revel in homoerotic churro consumption, boner slaps and dizzying trick shots with a camera embedded in a tennis ball. You can stop there. You can enjoy that. You could argue with me and say – for sure – this is actually the level the film is operating on, and anything more would be reading too much into a palatable thing. Yet the psychological threads accumulate, as do the questions power as they pertain to repeating assertions on class, elitism, the positioning of tennis as a sport practiced – largely – by the rich, and how Tashi sits – as a woman of color both manipulating two white men and driving, fiercely, towards a beige-shrouded life as a face of a fabulously exclusive UK car company.

There’s an essay to be written there, and it’s one more interesting than all the articles popping up interpreting the film’s ambiguous ending. But here’s the thing – ultimately Challengers serves up everything Tashi wants: some really good tennis, the volleying of the relationships relentless in its antagonism, and no matter how the match finishes: she wins.

You must be logged in to post a comment.